Summary

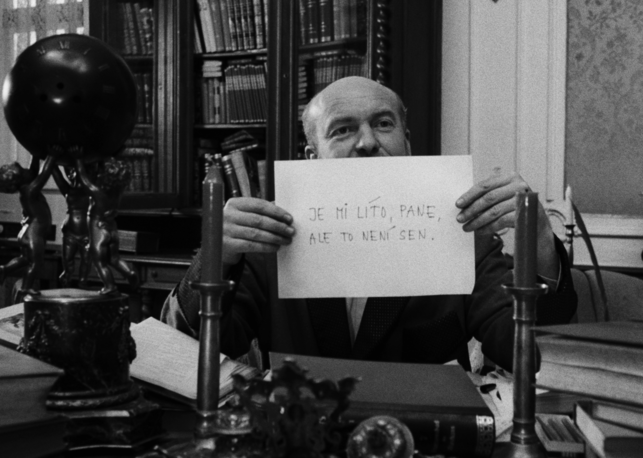

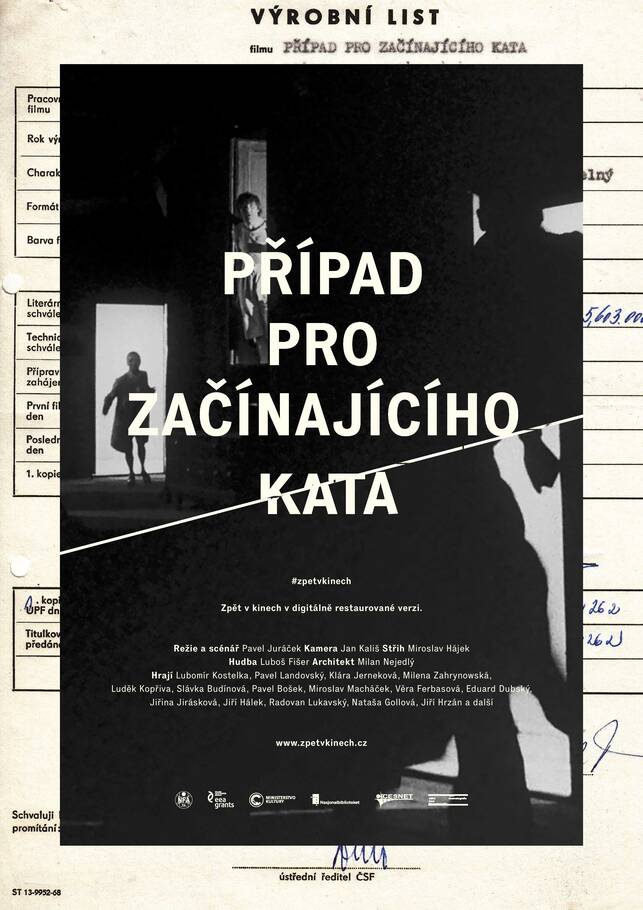

Both through his screenwriting and directing, Pavel Juráček made an indelible contribution to the New Wave of Czechoslovak cinema. Films directed by others according to his screenplays formed the mainstay of this singular author’s legacy, who, as it happens, himself directed only this one full-length feature film. The revolutionary and absurd drama Postava k podpírání (A Character in Need of Support, 1963) is after all a short film and Každý mladý muž (Every Young Man, 1965) consists of two unconnected short stories. As a screenwriter, Juráčka boasted a very particular personality. He was capable of equipping a fantasy genre story with all the features required for a spectacle that would appeal to the viewer, yet he would also give it a palpable metaphoric dimension: this was demonstrated by sci-fi picture Ikarie XB 1 (Icarus XB 1, 1963), post-apocalyptic drama Konec srpna v hotelu Ozon (The End of August at the Ozone Hotel, 1966) and the acerbic historical romance Bláznova kronika (A Jester’s Tale, 1964). Případ pro začínajícího kata (Case for the New Hangman, 1970) is a free adaptation of Jonathan Swift’s satire Gulliver’s Travels (first published in 1726). It is Juráček’s first and only full-length masterpiece as a director. The main character Lemuel Gulliver (Lubomír Kostelka) finds himself in the strange country of Balninarbi, where he constantly offends local customs and regulations. When interrogated, he is, moreover, incapable of providing a satisfactory explanation as to why he is not Oskar the hare, despite being in possession of the hare’s watch (which he found in the waistcoat pocket of the run-over animal). He’s condemned to death, but an invitation to the stranger from Laputa – the flying capital that is the home of the kingdom’s rulers – grants him a reprieve. Lemuel’s subsequent discovery that Balnibardi has not had a government for a very long time does not, however, improve his position vis-à-vis the local inhabitants, who derive self-assurance from their perceived existence of those “above”. Balnibardi, which constitutes an absurd mirror of the everyday communist reality experienced by Juráček, is not interested in the truth. To admit to having lived a life of self-deception and lies is plainly unpalatable for the locals… The sarcastic, surrealist playfulness and darkly amusing humour make Juráček’s feature film stand out from among a host of coded, symbolic cinematic works that accompanied the end of the 1960s (such as Evald Schorm’s Den sedmý, osmá noc [The Seventh Day, the Eighth Night, 1969] and Věra Chytilová’s Ovoce stromů rajských jíme [We Eat the Fruit of the Trees of Paradise, 1969]). It was all the more reason why Případ pro začínajícího kata could not find favour with the censors. The “normalisation” period of Czechoslovakia was under way and the film ended up in the “vault”, barred from distribution.

Read more