Summary

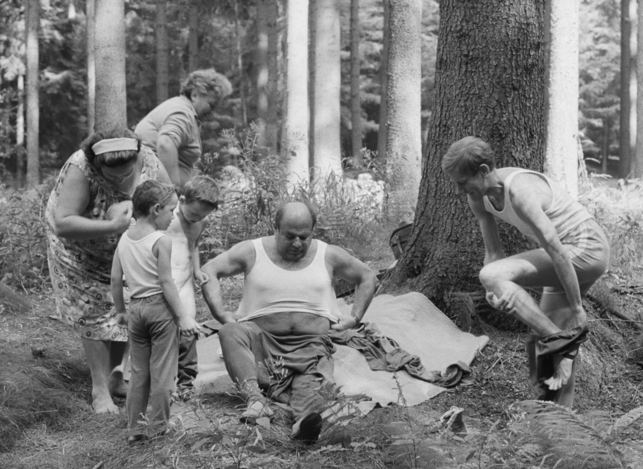

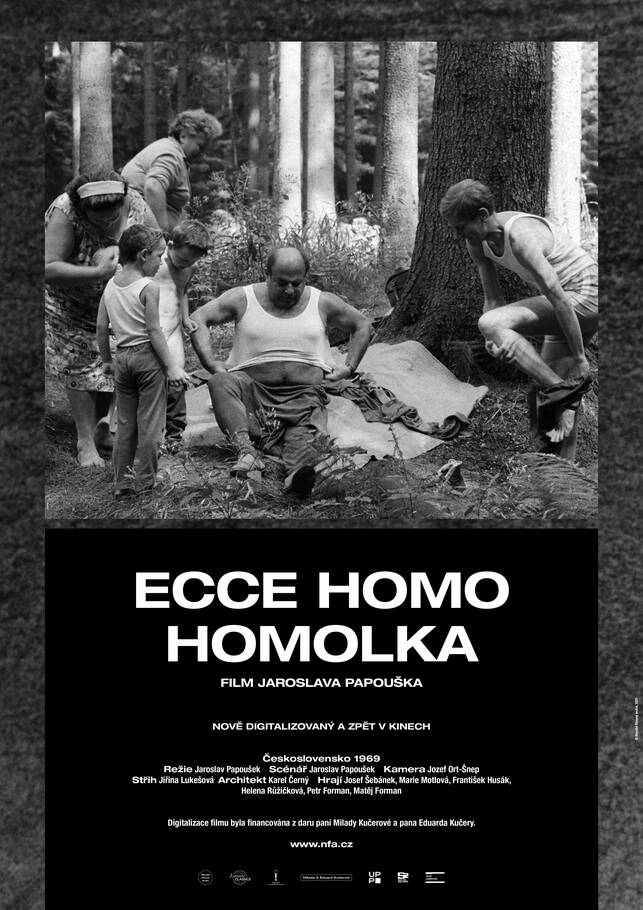

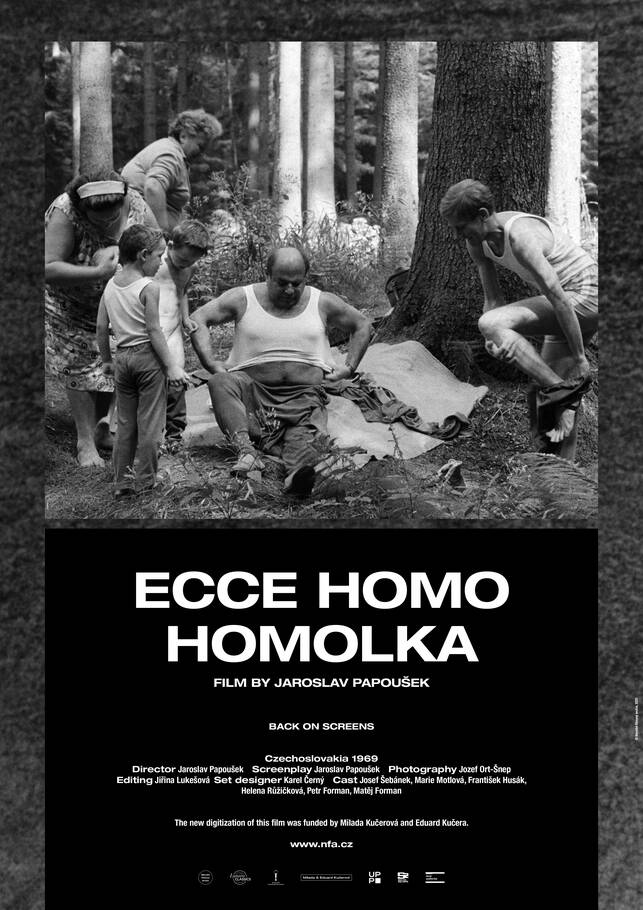

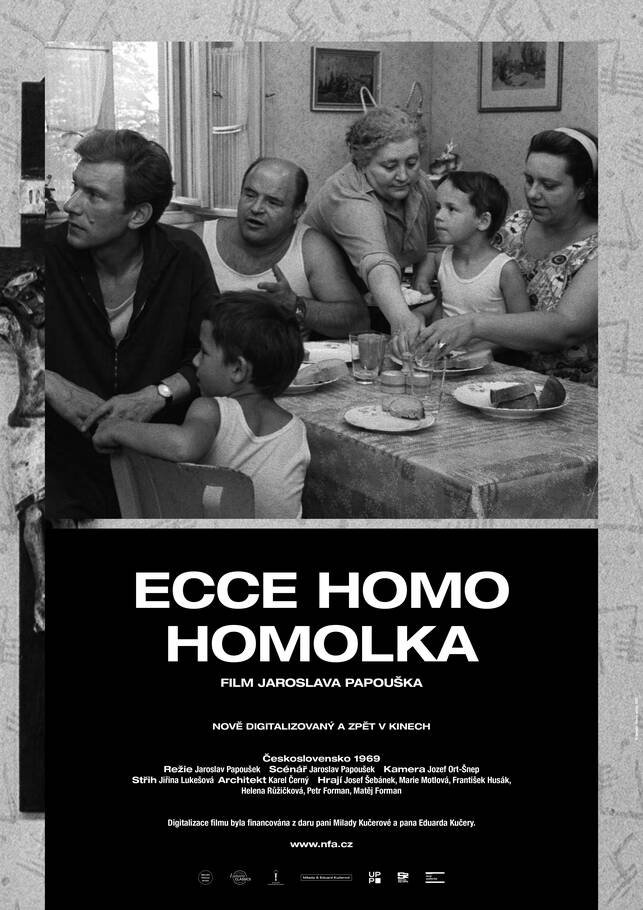

For many years, Jaroslav Papoušek was seen as the last of the Forman school trio. He did not debut as a director until several years after Miloš Forman and Ivan Passer. His wry comedy, The Most Beautiful Age (1968), in which he drew from his experience studying sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, showed great promise. Papoušek’s distinctive talent was confirmed in his family study, Ecce Homo Homolka (1969), completed after Forman and Passer had emigrated. In portraying the typical Prague family, Papoušek proved himself to be a comparably capable representative of the Czech realist school. The Homolkas leave the city for their Sunday trip to the countryside, where They find none of the things they base their existence on, i.e. neither peace nor comfort. Their vision of an idyllic end to the week is gradually eroded by shock waves of shouting, injustice and self-pity due to their inability to care for anyone other than themselves. A biting study of petty bourgeois pillars of contented urbanity, it relies for the most part on authentic dialogue, much of it popularised over the years, plus the natural acting talents of Josef Šebánek, Helena Růžičková, František Husák and Marie Motlová. Miloš Forman’s sons, Matěj and Petr, appear in the role of wayward twins. The film’s authentic expression is helped by the editing of Jiřina Lukešová, who worked on the most wellknown New Wave films, and the cinematography of Jozef Ort-Šnep, who had previously worked on Karel Vachek’s documentaries. The film premiered in March 1970 and was one of the last echoes of Czechoslovak New Wave. When the two sequels, Hogo Fogo Homolka (1970) and Homolka and the Purse (1972), came out, it was already evident that they were made after the “restoration of order”. While the Homolka family dynamic remains just as toxic in these films, the relentlessly satirical portrayal of Czech passivity, small mindedness and complacency is largely replaced by more popular gags.